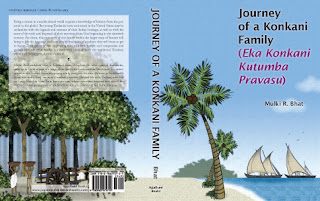

Several books that I have edited within the last couple of years are now being published. The latest one is Journey of a Konkani Family. If you're looking for an objective book review, you won't find it here, because I consider it an honor to have worked on the book and like it quite a bit. What you will find here, though, are reasons to pick up the book yourself.

Several books that I have edited within the last couple of years are now being published. The latest one is Journey of a Konkani Family. If you're looking for an objective book review, you won't find it here, because I consider it an honor to have worked on the book and like it quite a bit. What you will find here, though, are reasons to pick up the book yourself.Author Mulki Radhakrishna Bhat, a Konkani from Udupi on the west coast of Karnataka, grew up in India as part of a large, close family with rich cultural traditions. He immigrated to the United States as a young adult in the 1950s, navigated its very different cultural traditions, and had a long career as a nuclear physicist. He is now retired from Brookhaven National Laboratory. He and his wife, Padma, who live on Long Island in New York, have one son, whose questions inspired him to tell the story of several generations of his family within the context of the Indian diaspora.

Mulki spent more than a decade doing research in the United States and in India, interviewing many members of his extended family, and then writing the book. And such an engrossing story it is, one that is liberally sprinkled with transliterated Sanskrit* and that explains many traditions. Here is a portion from appendix 5 about the traditions involved in naming babies:

There are elaborate rules for choosing a baby’s name that are based on the time of birth or on astrology and local customs (Kane 1974, 2:234–55; Pandey 1969, 78–85). The customs and traditions of names have changed significantly from the Vedic age to the present. Some of these are discussed in Appendix 3: “Atri Gotra, or Clan Atri.” The current orthodox [Gauda Sarasvat Brahmana] custom is to give five names: one based on the family deity, one on the month in which the baby was born, one on the baby’s asterism, a secret name, and a customary name for daily use. The secret name is known only to the parents until the age of initiation and is whispered in the baby’s ear. The secrecy is to prevent its use by any malefactor who would perform sorcery to harm the baby. Parents have to remember the secret name, which is revealed at the time of the upanayana. The custom of using twelve names at a barso is not required by codes of law and has grown to be a tradition in some families. Boys used to be named after their paternal grandfather, whether that ancestor was alive or dead. Nowadays, some of these names are considered old-fashioned and other more modern names are used. There is much greater freedom in choosing a name for a girl. Usually, girls are named after a flower, a desirable virtue, or one of the exemplary women of Hindu epics.

Having roots in both the traditional Konkani world and the modern American world, Mulki tells the humorous tale in chapter 5 of his first encounter with American football, the U.S. religion, as part of an orientation for Indian immigrants:

Ohio State University (OSU), founded in 1870 as a land-grant university, had about 20,000 students when I joined in 1956. After being admitted for the fall semester, all of the foreign students gathered in a huge hall to get a general introduction to university life. ...

Football at OSU was not just a collegiate sport; it was the religion, with all of the attendant rituals. Out of curiosity, I bought a season ticket the first year to find out what all of the fuss was about. Attendance at a couple of games left me totally unmoved. All I could make out of the action was that there were two groups of huge men who looked like gorillas in armor, and they fought for the possession of one football. Somehow all of the nuances of the game were lost on me. I decided that attending games was a waste of time, so I gave away my ticket to the first person who asked for it. The OSU Buckeyes were almost professional football players masquerading as students, according to some critics. The weekly highlight of the religious observance was the Saturday afternoon football game, in which the powerhouse Buckeyes usually annihilated any opposing team, to no one’s surprise. Every OSU victory was celebrated by the ringing of the Victory Bell (a gift of the classes of 1943, 1944, and 1954), weighing 2,420 pounds and residing 150 feet from the ground on the ramparts of the southeast tower of the OSU stadium, to announce to the faithful another triumph of good over evil. The believers claimed that on a clear day,the bell could be heard five miles away. The whole university, including all of its libraries, closed down for Saturday-afternoon home games. When a few of us requested that the university’s main library be kept open on Saturday afternoons, this “heretical depravity” caused quite a stir. The university did open the library, but this grave anomaly was not publicized. The Buckeyes’ archenemy was another football powerhouse—the University of Michigan Wolverines, at Ann Arbor, Michigan. The OSU–Michigan game, which usually ended the football season, was a drama of cosmic proportions—the ultimate battle between good and evil. Over the years, this game had acquired its own mythology, saga, and portion of the faithful. Presiding over all of these observances was the head football coach, Wayne Woodrow “Woody” Hayes (1913–1987), now of blessed memory, a cult hero elevated to the semidivine status of guru by university alumni and the residents of Columbus. For most of the alumni, these games were the most important things that ever happened to them during their university years. Any other skills or knowledge they picked up was incidental or unintentional. I learned this from a letter I got from the OSU Alumni Association Club of New York City inviting me, as an alumnus, to attend one of their collegial meetings where movies of past Buckeye victories were to be shown, and of course they would all end with the joyous ringing of the Victory Bell and the singing of the Buckeyes’ fight song. These alumni wanted to savor every moment of past football victories, once more with feeling. It was truly an amazing bit of juvenile nostalgia. Unfortunately, as a nonbeliever in all rituals, I had to pass up this happy occasion.

Football at OSU was not just a collegiate sport; it was the religion, with all of the attendant rituals. Out of curiosity, I bought a season ticket the first year to find out what all of the fuss was about. Attendance at a couple of games left me totally unmoved. All I could make out of the action was that there were two groups of huge men who looked like gorillas in armor, and they fought for the possession of one football. Somehow all of the nuances of the game were lost on me. I decided that attending games was a waste of time, so I gave away my ticket to the first person who asked for it. The OSU Buckeyes were almost professional football players masquerading as students, according to some critics. The weekly highlight of the religious observance was the Saturday afternoon football game, in which the powerhouse Buckeyes usually annihilated any opposing team, to no one’s surprise. Every OSU victory was celebrated by the ringing of the Victory Bell (a gift of the classes of 1943, 1944, and 1954), weighing 2,420 pounds and residing 150 feet from the ground on the ramparts of the southeast tower of the OSU stadium, to announce to the faithful another triumph of good over evil. The believers claimed that on a clear day,the bell could be heard five miles away. The whole university, including all of its libraries, closed down for Saturday-afternoon home games. When a few of us requested that the university’s main library be kept open on Saturday afternoons, this “heretical depravity” caused quite a stir. The university did open the library, but this grave anomaly was not publicized. The Buckeyes’ archenemy was another football powerhouse—the University of Michigan Wolverines, at Ann Arbor, Michigan. The OSU–Michigan game, which usually ended the football season, was a drama of cosmic proportions—the ultimate battle between good and evil. Over the years, this game had acquired its own mythology, saga, and portion of the faithful. Presiding over all of these observances was the head football coach, Wayne Woodrow “Woody” Hayes (1913–1987), now of blessed memory, a cult hero elevated to the semidivine status of guru by university alumni and the residents of Columbus. For most of the alumni, these games were the most important things that ever happened to them during their university years. Any other skills or knowledge they picked up was incidental or unintentional. I learned this from a letter I got from the OSU Alumni Association Club of New York City inviting me, as an alumnus, to attend one of their collegial meetings where movies of past Buckeye victories were to be shown, and of course they would all end with the joyous ringing of the Victory Bell and the singing of the Buckeyes’ fight song. These alumni wanted to savor every moment of past football victories, once more with feeling. It was truly an amazing bit of juvenile nostalgia. Unfortunately, as a nonbeliever in all rituals, I had to pass up this happy occasion.

Beyond the tales of his own experiences, Mulki recounts and discusses how events in history affected his family and the culture of his ancestors, making it clear that people are not that different from each other, wherever they may live.

I was fortunate to work with three colleagues on Journey. Stephen Tiano handled book design and layout; Dick Margulis handled book production, publication, and marketing; and Venkatesh Krishnamoorthy proofread the book.

Journey of a Konkani Family, by Mulki R. Bhat, from Ajjalkani Books. Trade paperback (ISBN: 978-0-9835757-1-9; US$34.95); 650 pages.

_____________

*Because the license that I purchased to use the transliteration typeface does not extend to being able to use it in this blog post, I have further transliterated the Sanskrit words in the book excerpts I have quoted here, using one of the typefaces available to me through Blogger.

cultural memoir Indian diaspora author EditorMom

7 comments:

Nice to know that you were part of the Journey of a Konkani Family. I received a copy from the author who is also my relative from my Dad's side. Now have started reading it with interest as to a great extent it is the story of our community, now spread all over the world.

Chetan, how wonderful to hear from a member of Mulki's extended family! I hope you enjoy the book very much.

Hi,

I myself being a Konkani, i was in search for a book which would throw light on the history of Konkani families over the past few generations...

The good part is i found this book on the net....and now the bad part, it is not available in India....:(

Any idea if there is a proposal to print it in Managalore for readers here in India?

-Ajit Kamath

Ajit, I will contact the author and ask him about printing in India, and then I will post his reply here.

Ajit, I now have answers from the author:

You can find a copy of the book at the World Konkani Center (WKC) in Mangalore. He sent a complimentary copy to the head of the WKC, Basthi Vaman Shenoy, in 2013. You can borrow the book from the WKC.

If you want a copy to keep, you can purchase one from the book's distributor, Whitehurst & Clark Book Fulfillment. You can find the mailing address for the distributor on this website:

http://www.journeyofakonkanifamily.com

Hi Katharine,

I happen to read it yesterday. My father in law was doing some research around the migration of Konkanis (GSB). We belong to GSB group in Kochi, Kerala.

This book was a pleasure to read and I could relate to manytings written in the book. I also could get deep insight into the migtarion oh GSBs, culture, language and many more things. In fact I almost read the book cover to cover in less than 2 days.

This is a stupendous effort and a story interlaced with facts , history and opinions. I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Mulki R Bhat for his effort.

Umesh Kamath

Umesh, I am so glad that you enjoyed Journey of a Konkani Family. I will convey your gratitude to the author.

Post a Comment